A Clever Horse, A Golem, and Why Lyft May Have a Dominant Network Strategy

Updated: Apr 17, 2019

Lyft’s IPO a few days ago generated a substantial amount of financial and general media attention. And while there was initial enthusiasm for the event itself, Lyft’s share prices have dropped (down 14% as of this writing) and there is significant skepticism about the maturity of its business model, its ability to drive growth and expand margins, and the impending IPO of Uber.

One of the most compelling arguments against Lyft comes from New York professor Aswath Damodaran, who noted “The business model is broken right now… The driver is a free agent. The customer is a free agent. There is absolutely no stickiness in the business, and they know it. That’s the basic problem I have with the ride-sharing business, not just Lyft.”

Damodaran hits on a key challenge with operating, scaling, and competing effectively with a two-sided marketplace business model: if multi-homing costs (the cost a user bears to use multiple ride-sharing apps in this case) are low, competition is likely to come down to pricing… on both sides. As James Currier of NfX points out, competing on lower prices for riders and higher fees to drivers leaves both Uber and Lyft in a pretty vulnerable spot.

But perhaps Lyft and its shareholders have a reason for optimism thanks to a horse named Clever Hans and a Golem.

First, however, a very brief primer on Uber, Lyft, and business strategy in a competitive environment. Uber was founded in 2009 and created a new market: the ride-hailing marketplace. As a two-sided platform, it connected people with cars (drivers) with people who needed rides. As Uber entered a new market and built awareness, it created strong cross-side network effects: the value of the platform to drivers increased as the number of riders increased, and vice versa.

Lyft was founded in 2012, also as a two-sided platform connecting drivers and riders. In short, Uber’s profits (or rather, the promise of profits) invited competition, as it should.

Interestingly, while Uber has raised an absurd amount of capital (repeatedly), Lyft’s founders have been more muted in their capital needs.

Where do business strategy and competition come in? Simply put, most traditional strategy consultancies will advise their clients to focus on competing either on cost and operational scale (think Walmart) or differentiation (think Mercedez Benz) in order to create a sustainable advantage.

The challenge for business strategists is that the recent conventional wisdom regarding two-sided platform strategy is that neither a cost nor differentiation position s nearly as compelling as the virtuous, self-reinforcing forces of network effects.

So, does differentiation in the form of platform quality matter?

Clever Hans and the Golem

In the late 19th century, a man educated a horse. The horse, known as Clever Hans, could perform basic arithmetic on command, correctly demonstrating the answer by tapping his hoof the appropriate number of times. To prove that it was not his trainer somehow tricking his audience, audience members were encouraged to ask their own questions while the trainer was absent. Clever Hans consistently answered correctly.

A psychologist was brought in to investigate, and uncovered that Clever Hans was not actually performing any calculations. Rather, Clever Hans had clued into his questioner’s subtle verbal and body language clues: Clever Hans would simply keep stamping his hoof slowly until he reached the correct number, at which point he could detect the questioner’s excitement at the arrival of the answer.

This effect is otherwise referred to as the Pygmalion Effect: the phenomenon in which others’ expectations — and their treatment of a subject – affect the subject’s performance. The Pygmalion Effect can be positive, such as with Clever Hans, or negative. The negative side of this — for instance, nerves that create self-doubt for a job candidate prior to an interview, leading to fumbling responses to questions — is sometimes referred to as the Golem Effect.

From Uber-ing to Lyft-ing

As a fairly frequent business traveler, I started using Uber several years ago. I found it simple to use, the drivers were friendlier than taxi drivers, and I appreciated how Uber took “friction” out of the system: the “taxi” came to me, I didn’t need to ask for copies of receipts, and I didn’t even have to take out my wallet to pay.

Recently, however, Uber has been disappointing. Driver quality varies greatly, resulting in longer wait times, longer transit times, and overall a wide variability in ride experience. Beyond this, drivers occasionally cancel; on the flip side, if a user cancels the ride (even quickly) because the wait time is longer than was advertised, Uber charges a cancellation fee. It can feel like getting nickeled and dimed.

I decided to try Lyft recently and, expecting the wait time to be longer than initially suggested, I called for a ride before I was ready. In short, Lyft gave me 3 minutes to arrive (which I missed) and then canceled on me. Aware that Lyft was likely tracking my poor rider performance, I realized “Uh oh. Lyft is strict! I better only call when I am actually ready.” I did so, and within a minute of requesting, another Lyft arrived.

At that moment, I thought, “Hmm… if Lyft has a strict on-time policy for riders… and a better way of estimating arrival time for drivers and holding them to it (which it seems to), this creates a wildly better experience for both sides.”

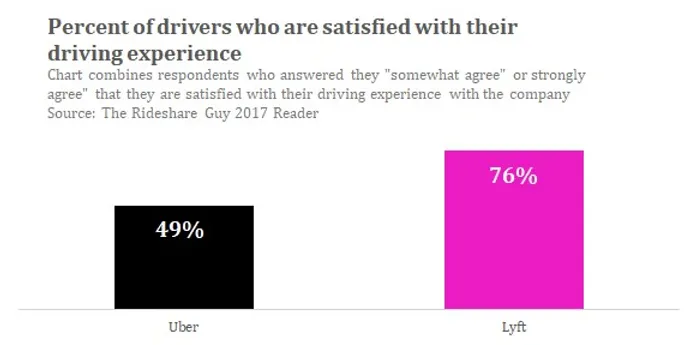

And if Lyft has those sorts of quality mechanisms in place, are there others? As it turns out, it seems quite likely: while more drivers still use Uber (75% primarily drive for Uber, vs 20% for Lyft), the numbers are almost equal in terms of which service drivers prefer to use (47% for Uber, 42% for Lyft). The higher relative proportion of drivers who prefer Lyft is not entirely surprising given that Lyft pays better, and that drivers report higher overall satisfaction levels with Lyft. I also recently learned that Lyft has a substantially more stringent registration process for drivers than Uber, which makes sense if it is focused on having a consistently higher quality rider experience.

Source: The Rideshare Guy Graphic by Summit Health

Lyft, Uber, Clever Hans and Golem

So how do Clever Hans and the Golem Effect come into play in the Lyft – Uber battle for rideshare dominance?

It comes back to reconciling classic business strategy with a two-sided network strategy. On the classic business strategy side, one way to attain a differentiation advantage is through product quality and user experience; as you deliver consistently, a company establishes brand strength, which is also a differentiator. On the two-sided network side, it is identifying a catalyzing force that compels individuals from one side to join your network (ideally only your network), which attracts the other side, which in turn attracts more of the first. If you can identify that catalyzing force or reason, you can create a massive virtuous cycle of self-reinforcing strength. The strength that may in fact create perceived multi-homing costs that New York professor Aswath Damodaran thinks are minimal.

Has Lyft identified rider and driver quality as such a catalyzing force?

Finally, it’s worth noting that Lyft is seeing results in terms of market share gains versus Uber:

Source: Second Measure

I have not confirmed my theory with Lyft, but consider the ramifications if Lyft is in fact pursuing a very intentional differentiation strategy:

By holding drivers to a higher standard (through higher registration requirements, higher service level expectations) and offering them better tools and higher pay, Lyft appears dedicated to creating a consistently higher quality rideshare product

By holding riders accountable (with firm time limits to meet your driver and perhaps other feedback mechanisms), Lyft is dedicated to creating a higher quality driver experience

Certain drivers and riders won’t meet Lyft’s quality threshold; but those who do will have a materially and consistently better experience than they will with Uber

Over time, this may create a self-reinforcing cycle: higher quality riders and drivers shift to Lyft, while those less focused on quality will migrate to Uber

Riders with higher quality expectations and willingness to pay shift to Lyft, while more cost-sensitive riders shift to Uber

As a result, Lyft should be able to exert substantially greater pricing power to less price-sensitive riders, while Uber is left with a lower quality product and less pricing power

There are of course many other factors to consider. Directionally at least, some appear to support this strategic thesis: among others, Uber has well-known brand and culture problems, and they have taken on so much capital to expand both geographically and in different product categories that they are unlikely to have focused on driving high quality network effects.

We know that quality matters in multi-sided platform businesses. Apple has an app review process to ensure its App Store maintains a minimum level of quality; while Google does not, it prominently displays user-generated ratings for each app in its Play Store. Both Apple and Google appear to have learned from Atari’s platform experience in the mid-1980s: Atari was the dominant video game console platform but its ecosystem crashed due to its lack of a developer or game quality review process, which allowed a plethora of low-quality games to flood the market.

Circling back to Clever Hans and the Golem Effect: it may just be that by limiting its focus, Lyft has become like Clever Hans: the people who show up expect a good experience, and Lyft has harnessed this to give them exactly what they expect. In doing so, Lyft is turning Uber into the Golem: riders less willing to pay for quality shift to Uber, which in turn attracts more drivers who can’t meet Lyft’s more rigorous standards and results in the lower quality experience that riders expect.

Helping MSPs to Transform Healthcare

At Summit Health, we have spent close to a decade as strategists and operators at the intersection of healthcare and of multi-sided platforms. We have done more than study multi-sided platforms; we have planned and executed commercial and market strategies, and helped develop new MSP products and scale them successfully. We are passionate about solving inefficiencies in the healthcare system, and believe MSPs offer tremendous potential to improve quality of care, reduce costs, and improve patient access to care.

If you are building a technology platform or network to bring together different healthcare stakeholders to interact with each other and break through opaque and inefficient processes, we’d love to hear from you — please comment or contact us!

Continue the conversation with Seth Joseph at seth@summithealth.io